A healthier life with wearables and health apps

Already taken enough steps today, got up regularly, trained? Ever since the Apple Watch and Fitbit, we’ve been familiar with those little “nudges” in favor of our health. However, wearables and apps have long been able to do much more. Their sensors collect millions of data from pulse to blood oxygen levels – not only for diagnosis but also for therapy.

It’s been 15 years since the technology magazine Wired discovered a quirky community of residents of Silicon Valley, the “Quantified Self Movement.” Tech nerds used digital devices to record the data of their daily life, such as daily step count, duration of their fitness training, body data, daily diet, and lifestyle habits. The goal was to lead a healthier, longer life through quantifiable lifestyle changes.

Today, this odd habit has gone mainstream. With Fitbit, the first digital bracelet came onto the market in 2009, which, together with smartphones, recorded the fitness data of its wearers. When Apple first introduced its Watch in 2015, it focused on its benefits for personal health. Watch wearers had to close three circles every day: the number of steps they took, getting up every hour (at least), and the calorie consumption from fitness training. Depending on the progress, the Watch sent encouraging or reprimanding reminders to stick to its self-selected program.

Since those early examples of “wearables” – digital devices worn on the body – the number of offers and their functions has exploded. When Apple launched its Watch, there were already 500 wearables with health functions on the market, which market researchers from CCS Insight put at $8 billion in sales. In 2021, wearables sales worldwide were already 29 billion US dollars. In 2019, Apple sold more watches than the entire Swiss watch industry.

Covid as a booster for wearables

The spread of wearables has received an additional boost due to Covid, the magazine The Economist recently diagnosed. With fitness centers closed, people took their fitness routines outdoors or turned the bedroom into their workout room. Wearables and apps help them get the most out of their activities. A Danish meta-study (the evaluation of over 100 individual studies) in the journal BMJ showed that the people covered by wearables walked around 1200 steps, approximately 800 meters, more every day during the pandemic years. Duration of fitness exercises increased by 49 minutes per week; time spent sitting decreased by 10 minutes per day. This seems like little progress. However, even 1000 more steps a day can reduce mortality by up to one-third in the best case.

Alert sensors

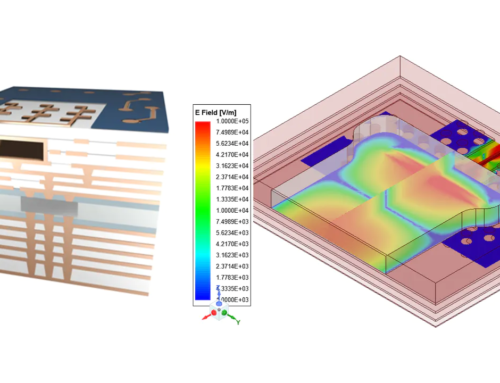

The ability of sensors to measure bodily functions is constantly increasing. Up until now, fitness applications have been at the forefront of wearables. But increasingly, monitoring our health is becoming an issue for these mini digital devices. Green, red and infrared LEDs on the underside of smartwatches or smart rings, worn like finger jewelry, register blood reflections as the blood pulses through the skin. The heart rate and, for example, cardiac fibrillation can be detected in good time. While fibrillation doesn’t have to be dangerous, it is a significant factor in stroke.

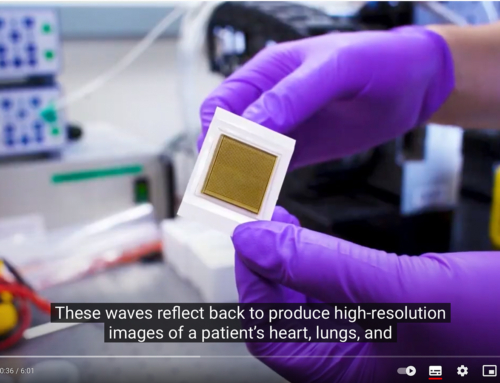

Red LEDs, in turn, can monitor blood oxygen levels, a key indicator of Covid. Smart plasters can measure the blood sugar level. While many of these features are built into popular consumer products, other wearables are explicitly developed for medical use. According to its manufacturer, the sensors from Rockley Photonics can measure hydration, sugar, alcohol, lactate, and other biomarkers, and body temperature and blood pressure. According to market observers, the market will be segmented into these two application areas: fitness and the general promotion of a healthier lifestyle on the one hand and medical control on the other.

Artificial intelligence and apps

The enormous amount of data supplied by sensors in smartwatches and fitness bands, chest and headbands and smart rings, in-ear headphones, and shoe soles need AI (artificial intelligence) to be processed and apps so that humans can ultimately use it can benefit. Diabetes is a logical application for blood glucose measurement and good management by the individual. In the meantime, performance-conscious people are also using the opportunities offered by blood sugar data: You can learn to avoid foods in your daily diet that cause a sudden rise and fall in blood sugar and trigger a sudden feeling of hunger.

Digital coach

Finally, the measurement of the self through a variety of data can also help therapeutically. One example is the Munich startup Kaia Health, which emerged from the painful experience of its founders, Konstantin Mehl and Manuel Thurner, with chronic back pain. After discovering multimodal therapy as an effective aid, they implemented it as digital therapy through an app. While the smartphone shows users the prescribed exercises, the selfie camera films the exerciser and evaluates the movements.

Thanks to artificial intelligence, the digital trainer gives feedback and encouragement to ensure exercises are done correctly. Studies show that digital instructions provided by Kaia’s app correspond to the quality of human physiotherapy. Today, the Kaia Health app is approved as a medical device by health authorities in the EU and the US.

According to The Economist, over 40 health apps are currently approved in the EU, ranging from diabetes, chronic back pain, opioid addiction, asthma, and anxiety. “Nag-Ware” (“annoying apps”) is the name given to applications that remind you to take medication or that there are still 1000 steps to go today. It doesn’t sound fascinating, but it can be of great help in the case of chronic diseases so that medication is not forgotten or discontinued after a short time. Other apps are digital coaches, like the Kaia Health app for chronic back pain.

More stories on this subject:

COVID & Co: Smart patches to fight infections

Share post: